By Alexa Dunbar Stewart and Casey H. Rawson

As public library workers, we understand that the library is not simply a repository for resources. Instead, as the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) asserts in its Public Library Manifesto, the public library is “a living force for education, culture and information” that “stimulat[es] the imagination and creativity of children and young people” (IFLA, 1994). This vision of the public library describes our roles as connectors, helping to facilitate learning that occurs at the intersections of academics, popular culture, and social justice. We have already discussed some of the foundational ideas and theories we need in our toolboxes to create such learning experiences for children and teens. In this chapter, we will explore a recently developed framework—connected learning—that synthesizes these ideas and can provide public librarians with a roadmap for creating powerful, engaging, and equitable instruction for youth.

What is Connected Learning?

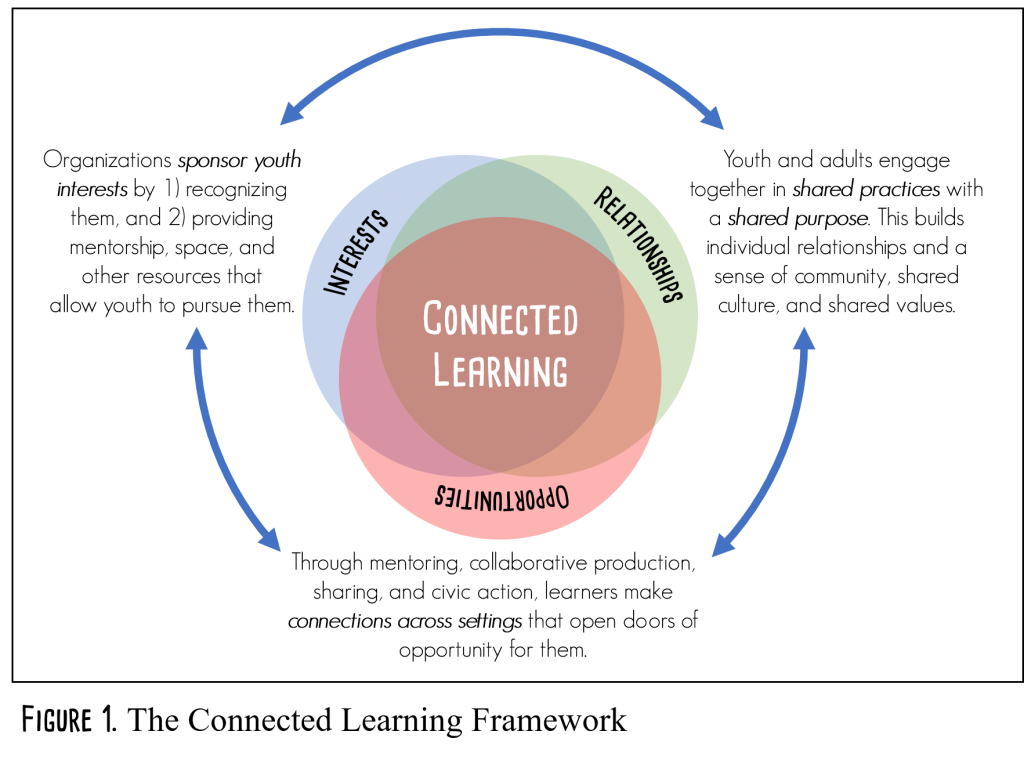

According to the Connected Learning Alliance (2018), “connected learning combines personal interests, supportive relationships, and opportunities. It is learning in an age of abundant access to information and social connection that embraces the diverse backgrounds and interests of all young people” (n.p.). This three-part focus on interests, relationships, and opportunities sets connected learning apart from the standards-driven, one-size-fits-all instruction often delivered in formal learning environments. Public libraries already incorporate some aspects of connected learning due to the way library programming is planned. Because public libraries want to get children and teens in the door, programs often focus on topics of popular interest, such as gaming, crafting and making, and pop culture. However, to fully implement the connected learning approach, an equal consideration of relationships and opportunities is required. The connected learning framework also emphasizes equity: Whose interests are prioritized? Who is offered the chance to build relationships? To whom are opportunities given, and to whom are they denied?

Connected learning is grounded in four key elements: sponsorship of youth interests, shared practices, shared purpose, and connections across settings (see Fig. 1, below). Again, these elements are not new to libraries, and some public libraries may already be incorporating some of them. Connected learning encourages public libraries to integrate all those elements into a seamless whole to maximize the learning of young people and to build supportive communities within and across library user groups.

Why Connected Learning?

You still may be wondering, “But why connected learning?” or “Is it really that beneficial?” The short answer to the second question is yes. Connected learning focuses on the learner. When instruction is learner-focused, it can also be more relevant, transferable, engaging, and meaningful. For example, consider the YOUmedia makerspace in the main branch of Chicago’s public library system. This site was one of the first spaces to explicitly adopt connected learning as a guiding framework, and youth in this space are encouraged to pursue their own interests using a wide variety of digital media production tools. Librarians, mentors, and youth themselves have reported numerous benefits of YOUmedia participation: Youth feel emotionally and physically safe in the space; they become more involved in their chosen interest areas; their digital media skills improve; they show improvement in communication and writing ability; and they become aware of additional post-secondary opportunities that they may never have been exposed to in other settings (Connected Learning Alliance, 2018).

Another reason connected learning fits so well with public library instruction is that it calls for and enriches connections to the larger community. Public libraries already have a focus on the community—at least in a general sense—as the community around the library typically defines its service area and user demographics. Many public libraries also collaborate with other community organizations, including schools, businesses. and non-profits. Connected learning both broadens and deepens our consideration of the library community by encouraging learning that:

- Connects individual children and teens to other community members for mentorship, collaborative production, and/or sharing;

- Leverages networked platforms and other digital tools to form communities of shared practice and purpose that transcend geographic boundaries;

- Creates, reflects, and/or reinforces shared cultures and values that respect the dignity of all community members; and

- Improves the quality of life within the community by including civic action components.

Finally, connected learning is beneficial to learners because it is a hands-on, minds-on way of learning. Connected learning has a focus on production and creation (Connected Learning Research Network, 2013). As learners collaborate, create and revise, and share their work, they authentically connect with each other and with the community outside the library. Children and teens learn the skills and content they need to move forward at the precise time they need it, providing rich context and purpose for learning.

To explore connected learning in detail, including what this approach might look like in the real world, we will discuss of the four key elements of connected learning and share examples of each within a public library context.

Sponsorship of Youth Interests

Youth interests form one of the three foundations of connected learning, along with relationships and opportunities. According to the Connected Learning Research Network (2013), “When a subject is personally interesting and relevant, learners achieve much higher-order learning outcomes” (p. 12). Public libraries have more flexibility to respond to learner interests compared to other learning spaces (such as school libraries) because public library learning is not guided by rigid standards and pacing guides.

People like Constance Steinkuehler, a game-based learning scholar, believe that interest-driven learning is not only valuable but also necessary for meaningful learning. She explained:

It’s kind of stating the obvious, but we forget it in schools all the time that if you care about understanding the topic, you will sit and work through, you will persist in the face of challenge in a way that you won’t do if you don’t care about the topic. What I’m trying to say is rather than treating kids’ interests as a means toward your educational goals, [try] to treat your educational materials as a means towards their goals. (Edutopia, 2013, n.p.)

In other words, the goal is not to hijack youth interests for the ultimate purpose of teaching children and teens information literacy content and skills. Instead, our goal should be to provide just-in-time information literacy instruction for the ultimate purpose of helping children and teens explore and deepen their own interests and passions. Public libraries can do this by first recognizing and validating the interests of the youth they serve, keeping in mind that those interests may change rapidly. Second, libraries can provide the resources, instruction, and space that youth need to pursue their own interests. These may take the form of mentors, texts, digital tools, protected library space, passive programming, physical making materials, and face-to-face programming developed in response to youth demand. See the real-world example below of Heather, who used her interest in Harry Potter to improve her own writing skills.

Spotlight: Sponsoring Youth Interests Through Fanfiction

Spotlight: Sponsoring Youth Interests Through Fanfiction

Heather Lawver was a teenager when she read the Harry Potter series for the first time (Jenkins, 2004). Her passion for the books led to her to become a part of the online fan fiction community. Fanfiction is unique in its ability to provide an openly networked audience for writing in a way that allows authors to build off each other to develop “authentic, interactive writing activities” (Black, 2005, p. 126).

Lawver started The Daily Prophet, a fan-created newspaper set in the Harry Potter universe (Jenkins, 2004). Lawver wrote for The Daily Prophet herself and took submissions for the paper, which was then published to a large fan fiction community. For Lawver and those like her, fanfiction was an opportunity not only to write about something she loved but also to develop a variety of skills, including vocabulary, sentence structure, grammar, editing, and revision. Some fanfiction writers have even gone on to publish online and physical books (within and outside of their fan fiction community), leading to the start of a writing career (Jenkins, 2004).

Heather Lawver is just one of many young people who share similar stories; fanfiction communities are made up of thousands or even millions of like-minded people from all over the world. Fanfiction communities embody all three foundations of connected learning: interests (authors write about whatever original media they choose), relationships (communities of authors and fans share feedback and encouragement with each other), and opportunities (individual writers and editors, often called beta readers, have the chance to improve their own skills, which are transferable outside of the fanfiction community).

Writing fanfiction is an interest in itself, which public libraries could support through writing workshops, online fanfiction networks hosted by the library, author visits from high-profile fanfiction writers, and easy access to mentor texts. Public libraries can also encourage children and teens with interests in existing media to explore writing or reading related fanfiction. Online communities such as Archive of Our Own (AO3) (https://archiveofourown.org/) host fanfiction writing for nearly every fandom imaginable, from the Avengers to Zootopia (though librarians should be cautious when directing children and teens to fanfiction sites, as some stories are intended for mature audiences). The ultimate goal of this work for public librarians is not to teach information literacy skills but to sponsor youth interests through the teaching of information literacy skills.

Shared Practices

While the connected learning framework does encourage unstructured “hanging out and messing around” (Connected Learning Research Network, 2013, p. 66), the core of the framework centers on purposeful and collaborative production. As the Connected Learning Alliance (2018) explains, “Ongoing shared activities are the backbone of connected learning. Through collaborative production, friendly competition, civic action, and joint research, youth and adults make things, have fun, learn, and make a difference together” (n.p.).

Librarians can play a role in establishing these shared practices. Think back to the Dewey and Dragons example shared in Chapter 1 (pages 2-5). Librarian Jamey Rorie established shared practices in that group by finding a volunteer Dungeon Master who provides consistency and structure to the group’s meetings; helping to build a culture of friendly competition among participants as they develop in their mastery of the game; connecting participants to additional texts, such as graphic novels, that enrich their individual and collective experiences of the game; and developing a group norm for welcoming new players to the group.

Connected learning acknowledges that in today’s world, some of the richest communities of practice are found online. Social media and other online platforms can encourage peer-supported learning as individuals learn with and from others who share their interests. This access to likeminded peers can help learners feel more comfortable asking questions or receiving critical feedback, both of which are critical to learning. Libraries can provide access to these communities for youth who may not have reliable internet access at home. As Beth Stone (2015) put it, “Digital tools help increase connectivity and access to information … [and] help decrease educational disparity.”

Shared Purpose

The third key element of connected learning emphasizes learners coming together for a shared purpose. This shared purpose goes beyond simply working together to accomplish some discrete task. As the Connected Learning Alliance (2018) explained,

Learners need to feel a sense of belonging and be able to make meaningful contributions to a community in order to experience connected learning. Groups that foster connected learning have shared culture and values, are welcoming to newcomers, and encourage sharing, feedback and learning among all participants. (n.p.)

The shared purpose can be a production-centered goal, an interest-driven learning objective, or a desire for civic change (Connected Learning Research Network, 2013).

Although these learning groups can be made up of same-age peers, they can also be made up of anyone that has a shared purpose with the learner (Connected Learning Research Network, 2013). This means that the people who make up a learning community may be of different ethnicities, races, ages, education levels, gender identities, sexual orientations, and socioeconomic levels, just to name a few. Learning communities that have a diverse population can offer varying levels of expertise and different viewpoints that are valuable for all learners.

Spotlight: Connected Learning on The Wrestling Boards

Spotlight: Connected Learning on The Wrestling Boards

Jonathan, a teenage boy from Europe, and Maria, a teenage girl from the Philippines, share little in common on the surface. Yet these two young people were brought together by a mutual interest in professional wrestling—an interest for which both teens faced stigma in their offline lives (Martin, 2015).

Both Jonathan and Maria found their way to The Wrestling Boards, a professional wrestling fan community. Maria, who was also interested in fanfiction, began writing for the community’s fantasy wrestling federation (a text-based role-playing game), while Jonathan learned Photoshop with the help of others on the site to create and share wrestling-focused images. Jonathan also adopted a mentoring role within the community, sharing, “I give and get feedback often about what I do. …. I often help/mentor new members of the forum to the best of my ability” (Martin, 2015, Peers Helping Peers section).

Within the Wrestling Boards community, common interests and ongoing practices—primarily writing, media production, and sharing—helped to create a rich community with shared norms, a supportive and friendly culture, and collaborative learning. For Maria and Jonathan, this community also gave them a sense of belonging and acceptance of an interest that was not encouraged in their offline interactions.

Connections Across Settings

As its name implies, connected learning is dependent on relationships and links. Within this framework, “connections” are interpreted broadly to include:

- Those that individual learners make between their existing interests and new learning,

- Those between and among individual learners,

- Those between individual learners and mentors or instructors,

- Those that tie together the larger community that the library serves,

- Digital connections to individuals, groups, and information online, and

- Those across organizations.

Public librarians can facilitate these connections in a variety of ways. Because we have access to a big-picture view of our community that individual children and teens may not, we may be aware of opportunities for connections that we can pass along to learners. We can also collect and highlight resources that help youth make connections for themselves, for example how-to texts about crafting or fanfiction. By staying abreast of popular and emerging online platforms, we can also help direct children and teens to communities where they can find the sense of belonging that Maria and Jonathan experienced on The Wrestling Boards.

In all this work, we must ensure that we strive to “connect with youth through the building of trusting relationships developed without judgment of their interests” (Martin, 2015, Connecting to Youth Interest section). For ideas about how to do this, review Chapter 2 (Knowing Your Learners).

Connected Learning and Library Instruction

Connected learning can and should have a place in public libraries. As described earlier in this chapter, public libraries are already incorporating connected learning in their instruction and programming. The Nashville Public Library (NPL) has a dedicated teen space with a maker lab, new technologies, and even a creative writing center (Libraries Transform, n.d.). The NPL uses their librarians’ knowledge to create instruction around these technologies, inviting in people from the community and their expertise, as well as encouraging peer relationships and support. The Seattle Public Library has a program called “Your Next Skill” where patrons request that their library hold a program focused on a particular skill (Libraries Transform, n.d.). Their librarians then create a program around this information to help their patrons learn what they want to know, while using technology and other library resources. Both of these libraries are taking steps to incorporate connected learning in their instruction, and they are seeing the benefits of designing programs with connected learning in mind.

Assessing Connected Learning in Public Libraries

The connected learning framework is still fairly new, and because it is so different from traditional classroom instruction, researchers and practitioners are still exploring its outcomes and developing best practices for evaluating the learning that results from this approach. One notable effort in this area is the work of the Capturing Connected Learning in Libraries (CCLL) group, which is a research and practice collaboration between the Los Angeles Public Library, the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA), the Connected Learning Research Network, and the YOUmedia Learning Labs Network. This project aims to “serve the needs of libraries by providing them with evaluation instruments, tools, and plans to understand and reflect on their effectiveness in implementing connected learning programs” (Connected Learning Lab, 2018). As of this writing, the CCLL group is still working to develop these tools.

Assessing connected learning in public libraries is necessary, as it is essential and useful to assess any type of instruction, regardless of the setting. However, it can be difficult to measure some of the connected learning principles. To get a comprehensive understanding of the outcomes for a connected learning initiative, qualitative approaches may be best. For example, conducting an informal interview with a teen participant will probably give you much richer information about what and how that teen has learned compared to a survey or an attendance count.

Criticisms of Connected Learning

Connected learning, like most instruction techniques, has its critics. In an article titled “What’s all the Fuss about Connected Learning?” Henry Jenkins (2013) stated that some people still have reservations about connected learning because they feel as though it takes focus away from academics and traditional literacies. This criticism is less relevant in public libraries than in formal education settings with a required set of topics that must be covered.

Some people also feel that connected learning’s emphasis on technology and online networks risks leaving out those who still lack access to reliable internet at home (Jenkins, 2013). While this is a valid concern, it is also an argument for public libraries to lead the way in connected learning implementation, as they can provide free internet access for all community members. It’s also true that connected learning does not require new technology or high-tech resources. If you can access your community (locally or online), you can still practice all four elements of connected learning. This is not an exclusively technology-focused approach; instead, it’s a framework for instruction, and it can be practiced with or without access to technology.

Conclusion

Connected learning is a valuable framework to practice in public libraries. The four elements working in concert allow the learner to develop 21st century learning skills, something that is necessary for school, work, and civic engagement (Connected Learning Research Network, 2013). Public libraries have a unique ability to provide instruction without a set of school-mandated standards, allowing for their instruction to be versatile and flexible. Public libraries already have many basic elements of connected learning in place; they just need to be brought together to maximize their effectiveness for the learner.

References

Black, R. (2005). Access and affiliation: The literacy and composition practices of English-language learners in an online fanfiction community. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49 (2), pp. 118-128.

Connected Learning Alliance. (2018.). What is connected learning? Retrieved from https://clalliance.org/about-connected-learning/

Connected Learning Lab (2018). Capturing connected learning in libraries. Retrieved from https://connectedlearning.uci.edu/project/capturing-connected-learning-in-libraries/

Connected Learning Research Network (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Retrieved from https://dmlhub.net/wp-content/uploads/files/Connected_Learning_report.pdf

Edutopia (2013). Constance Steinkuehler on interest-driven learning (Big Thinkers Series). Retrieved November 20, 2017, from https://www.edutopia.org/constance-steinkuehler-interest-driven-learning-video

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) (1994). IFLA / UNESCO public library manifesto. Retrieved from https://www.ifla.org/publications/iflaunesco-public-library-manifesto-1994

Jenkins, H. (2004). Why Heather can write. MIT Technology Review. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/s/402471/why-heather-can-write/

Jenkins, H. (2013). What’s all the fuss about connected learning? Retrieved from http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2013/01/whats-all-the-fuss-about-connected-learning.html

Libraries Transform. (n.d.). Connected learning. Retrieved from http://www.ilovelibraries.org/librariestransform/connected-learning

Martin, C. (2015). Connected learning, librarians, and connecting youth interest. Journal of Research on Libraries & Young Adults, 6. Retrieved from http://www.yalsa.ala.org/jrlya/2015/03/connected-learning-librarians-and-connecting-youth-interest/

Rheingold, H. (2016). Assessing, measuring connected learning outcomes. Retrieved from https://dmlcentral.net/assessing-measuring-connected-learning-outcomes/

Stone, B. (2015). Connected learning: How is mobile technology impacting education? Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2015/12/01/connected-learning-how-is-mobile-technology-impacting-education/